The Eurovision song contest voting patterns is a popular theme for the analysis of European identity and culture. In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (September 2013, Volume 4, Issue 2) Dimitris Ballas, Danny Dorling and I looked at the voting patterns of this year’s contest that was held in Malmö (Sweden). It has long been argued that there are clear patterns based on geographical region as well as cultural and linguistic bonds and there has typically been labelling of groups of countries that give their votes to each other as ‘blocs’ such as the ‘Scandinavian bloc’, the ‘Mediterranean’, ‘Western’, ‘Eastern’, ‘Scandinavian’, the ‘Balkan’ bloc etc. It can also be argued that political considerations may also affect these voting patterns and this may be particularly interesting in the recent Eurovision song context with voting patterns possibly influenced by the on-going political and economic crisis in the European Union (EU). This map series puts a focus on those countries being closely associated with the EU, either by being current members or official candidate member states (or official potential candidate for EU accession) and/or signed up to any of the following agreements: European Economic Area, the Schengen Zone, the European Monetary Union. The maps are based on European states that currently meet at least one of these criteria, leaving the remaining participants of the song contest aside.

The Eurovision song contest voting patterns is a popular theme for the analysis of European identity and culture. In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (September 2013, Volume 4, Issue 2) Dimitris Ballas, Danny Dorling and I looked at the voting patterns of this year’s contest that was held in Malmö (Sweden). It has long been argued that there are clear patterns based on geographical region as well as cultural and linguistic bonds and there has typically been labelling of groups of countries that give their votes to each other as ‘blocs’ such as the ‘Scandinavian bloc’, the ‘Mediterranean’, ‘Western’, ‘Eastern’, ‘Scandinavian’, the ‘Balkan’ bloc etc. It can also be argued that political considerations may also affect these voting patterns and this may be particularly interesting in the recent Eurovision song context with voting patterns possibly influenced by the on-going political and economic crisis in the European Union (EU). This map series puts a focus on those countries being closely associated with the EU, either by being current members or official candidate member states (or official potential candidate for EU accession) and/or signed up to any of the following agreements: European Economic Area, the Schengen Zone, the European Monetary Union. The maps are based on European states that currently meet at least one of these criteria, leaving the remaining participants of the song contest aside.

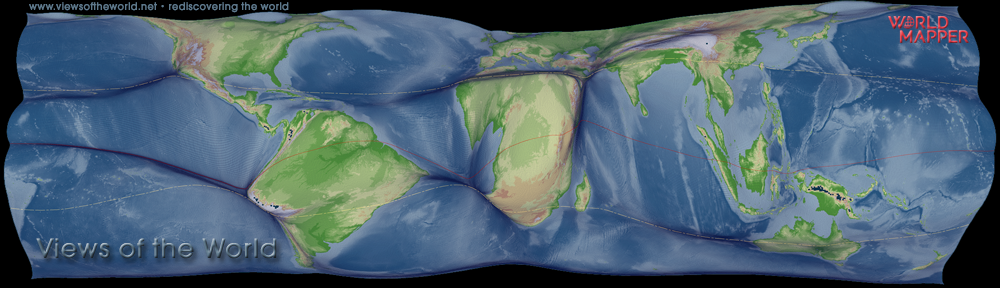

The reference map shows a population cartogram of this area where each country is resized according to its total population. All other maps are drawn relative to the number of Eurovision points a country received. It should be noted that not all countries took part in the final round of the contest or in the voting. Each country has to give 12 points to its favourite song, 10 points to the second favourite, 8 to the third and 7 to 1 points in descending order to the remaining seven ranked songs. These points are allocated via telephone voting and all countries taking part in the final and the two semi-finals are eligible to vote.

The map of the total number of votes is dominated by the winner Denmark, which received a total of 281 points, 90 more than the second country in our focus area, Norway.

The remaining maps show the number of points that all countries gave to an individual country. They highlight these patterns for the votes that were given to Denmark, Germany (18 points), the United Kingdom (23 points) and Greece (152 points).

The voting behaviour for Germany and the United Kingdom show a very polarised pattern which – putting aspects of the quality of the performance aside – also reflects some of the persisting affinities but also very contemporary hostilities or irrelevance in a European context. Germany mainly relies on its neighbours and places where there may be a larger numbers of German expats or tourists at the time of the contest, the latter of which could also apply to the British result. Germany is widely seen as a political scapegoat at the moment, while the relevance of Britain within Europe is seen less important, which could help to explain why the received so few votes.

The map of votes for Greece, which at many times has also been at the very centre of political and economic attention within Europe and internationally in the past three years, shows a total of 152 points. Greece received 12 points from Cyprus and San Marino, 10 from Albania and 8 from Montenegro, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

Here are the bibliographic details:

- Hennig, B. D., Ballas, D. and Dorling, D. (2013). Voting for Europe: Eurovision 2013. Political Insight 4 (2): 38.

Article online (Wiley)

The content on this page has been created by Benjamin Hennig. Please contact me for further details on the terms of use.