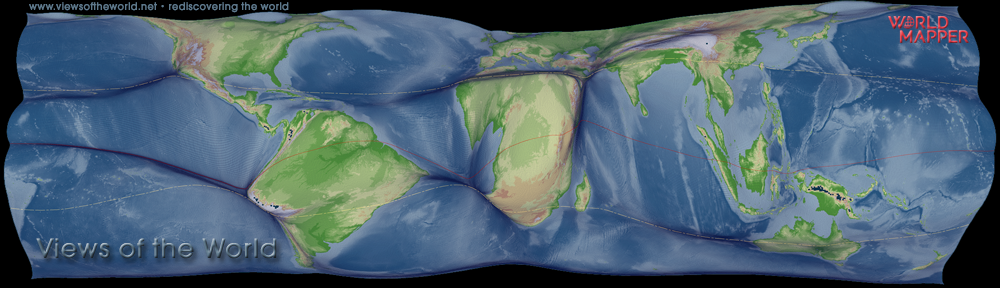

Following the foundation of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1890 the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens mark the beginning of the modern Olympic Games. 14 nations and 241 athletes competed in 43 events back then. The number of participating nations, of athletes and awarded medals has grown ever since. At the 30th Summer Olympics in London this year, 204 nations participated with 10,820 athletes who competed for medals in 302 events. After mapping the picture of this year’s event, it is also interesting to see how the modern Olympics of all time compare, with some interesting differences but also persisting patterns of success. The following map series shows where all the medals of the Olympics in the past 116 years went to (with the main map combining Summer and Winter games, and the two smaller maps showing the two separately):

The data shown in these maps comes from a compilation of records in the IOC database as compiled on Wikipedia (current as of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London). In order to make the map transformation work, some adjustments to the data were necessary to reflect today’s territorial borders. The main aim in the adjustment was to include as many of all medals as possible, while retaining our understanding of the world as we see it today. The main redistribution of medals for countries that no longer exist therefore followed two strategies: Where a country that does not exist anymore has a successor, the data for that country were merged with today’s successor of this country (such as the German Democratic Republic which was merged with the data for Germany, or – slightly more disputable – the data for Soviet Union being assigned to Russia). In other cases the medals for a no-longer existing country were redistributed over all succeeding countries in equal parts, such as the medals for Yugoslavia which were given to Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, and Serbia & Montenegro. Only those medals not being clearly associated with a country (either of today or of the past) were left out in this map (such as those of the Mixed Teams of the early days.

A second map series has been created from the total number of participations at the modern Olympics, with a similar redistribution of data but here fully counting participation for every succeeding nation equally where it makes sense (so e.g. Germany does not get more participation counts as it has been participating parallel to East Germany, while all succeeding countries of Yugoslavia get one participation for every time Yugoslavia took part in the Olympic Games). This is the shape of the Olympic world showing the countries resized according to the total number of participation at the modern Olympic games:

The two map series show the patterns that shape the history of the modern Olympics. In terms of mere participation, the Olympic world is far more equal than one would perhaps suspect (Europe dominating the participation is mainly caused by its large number of nations, but an absolute equal participating would look like this map on Worldmapper), although the total number of participating athletes would quite certainly provide a much more polarised image (more like the one drawn from this year’s Olympics). But at least the event is a little bit about the world coming together, which hardly ever happens in such a (more or less) harmonic way. The differences between Summer and Winter Olympics certainly reflect more the climate conditions in the world, with Winter sports being much more prominent in the Northern regions of the planet.

The real Olympic inequalities are in the medal tables and shown in the medal maps above: In large, these are a reflection of wealth distribution in the world, raising the question whether money can indeed buy sporting success (it cannot always do that though). Smaller are also the differences of medals between the Summer and Winter games with a few obvious observations such as Australia doing worse at the Winter games putting countries like Canada, Norway or Austria more prominently on the map there. But overall, summer and winter alike, the medals often go where the money is.

Besides investment in sports by those countries who can afford it, the medal tables also reflect a battle for global supremacy in political terms. The heyday of the Cold War still leaves a lasting legacy in the all-time medal map where “the relative power of the United States and the Soviet Union were regularly measured in gold, silver and bronze” (The Economic Times). Looking at the 2012 medal map we see a new power emerging on the world stage, with the battle for the top spot in the medal table now being fought between the USA and China (and China slowly catching up with its GDP growth). In the all-time medals, there is still some work to do for China, but the picture will certainly change over the next decades.

The Olympics are about much more than only sports. They tell us a lot about our changing economic and political world…

The content on this page has been created by Benjamin Hennig. Please contact me for further details on the terms of use.