My research on gridded cartograms has its roots in the works of the Worldmapper project, which was originally released in 2006/07 and extended in the following years. While the first phase of the Worldmapper project has visually describes the world, mapping the national contours of hundreds of variables, it did so only in one way and a way easily open to criticism despite its novelty and wide scope. To tackle this, I conducted further research to help address these potential criticisms, to work on moving the resource beyond its simple descriptive form. This included a look at more theoretical issues of how world resources, flows and shares are understood, particularly visually understood – and how this can be improved.

The gridded cartograms are one of the key results of this second phase of the Worldmapper project to advance and improve the capabilities of the Worldmapper maps. So far we integrated gridded cartograms on the Worldmapper website only in form of the World Population Atlas that shows an extensive collection of gridded country cartograms. These are the first ever made compilation of maps showing population distributions in cartogram form at that level of detail for every country of the world, but there is more to the underlying technique than this.

Following the release of these first maps using a gridded cartogram approach, I have made progress not only in enhancing the accuracy and quality of these country-level maps, but also in advancing the technique to a stage where gridded cartograms can be utilised as an alternative map projection (explained and discussed in full detail in my PhD thesis). Some examples are shown on this website: One example for the new capabilities at country level is the map of population changes in Germany. At global level the example of agricultural spaces presented at last year’s Annual Meeting of the Society of Cartographers demonstrates their applicability not only for population-related issues, but beyond that for other quantitative dimensions with a new level of detail, but also new capabilities of showing additional layers of information that the original Worldmapper approach was not capable of achieving.

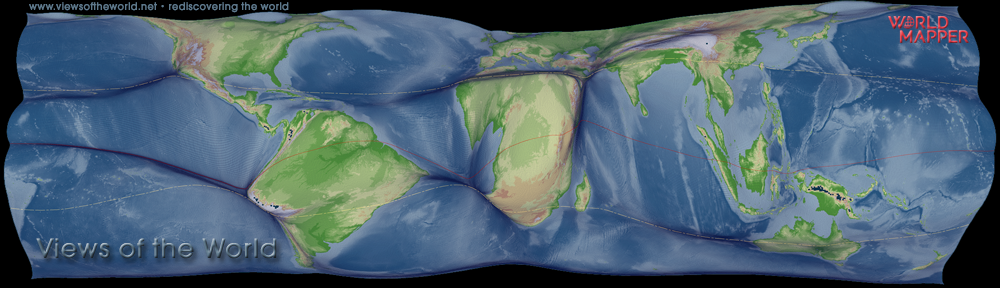

There sometimes is a certain confusion about the differences between the maps drawn in the first stage of the Worldmapper project (and that we carry on producing as well), and the new gridded cartograms. The following map series shows the differences by using the Worldmapper colour scheme applied to the different map types (for full clarity, the map series starts off with a conventional map projection):

The two cartogram depictions are both based on the same underlying principle of a diffusion-based algorithm developed by Gastner/Newman, but take a very different way of applying this principle. The comparison of the two maps showing population distributions (and a look at a normal map) makes this very apparent: The original Worldmapper approach results in a relatively easy to read map depiction (which can vary in its character depending on the topic depicted – some of the most extreme disoroted maps are harder to read). This is because it preserves the country shapes, one of the great advantages of Gastner/Newman’s approach. Anyone being familiar with the shapes of the countries will be able to adapt to the depiction in a fairly easy manner (although this approach becomes more difficult when administrative areas that a map reader is less familiar with are transformed with this method – borders are arbitrary lines drawn by humans, and only the knowledge where these borders are helps to read these maps).

In contrast to that, the gridded cartogram shown on the bottom shows more unusual shapes – the colours help to see that e.g. China is now extremely distorted within its borders. A closer investigation of this map (better seen in the enlarged version of the map series) shows the individual grid cells within this map projection that are the base for the transformation, depending on the number of people living in an area. That explains, why there is a distortion within countries, as people are not evenly distributed within a country. In the case of China, the major share of its more than 1.3 billion people squeezes into the eastern provinces, rather than the sparsely populated western region.

This map series demonstrates the principle and differences between the different density-equalising cartogram approaches. It explains, why one map is easier to read, but not suitable for advanced applications, while the gridded cartograms look a bit more complicated to read at first, but therefore contain a much higher level of detail that gives these maps equal capabilities of serving as a basemap for other geographic information that can be projected on top of these maps.

That, in short, explains the different stages of the Worldmapper project so far, and the evolving nature of the maps between the launch of the project website in 2006 and the completion of my PhD research in 2011. As for the future of Worldmapper, the first two phases have only marked the beginning. We hope to start work on a new Worldmapper that does not only contain updated maps of the existing >700 themes, but also extends the range of mappings towards a collection of gridded cartograms of which the more regular visitors of this website have seen some examples since I started doing this blog. Until then, please do visit Viewsoftheworld.net again if you want to see new material.

Any support, comments or suggestions on Worldmapper are always appreciated and welcome: info@worldmapper.org (we do read all emails, even if we can’t answer all of the inquiries we get)

The map series on this page has been created by Benjamin D. Hennig. It is a modified version of a figure included in the book Rediscovering the World: Map Transformations of Human and Physical Space (Springer 2013).

The content on this page has been created by Benjamin Hennig. Please contact me for further details on the terms of use.