Following the full cartographic roundup of this year’s general election earlier this week, here comes a related piece of research. In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (September 2015, Volume 6, Issue 2) Danny Dorling and I plotted the geography of an unexpected Conservative General Election victory.

Following the full cartographic roundup of this year’s general election earlier this week, here comes a related piece of research. In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (September 2015, Volume 6, Issue 2) Danny Dorling and I plotted the geography of an unexpected Conservative General Election victory.

What happened of most importance in 2015 was the rapid acceleration of a trend that has been underway in UK voting since 1979 and can be seen as having its origins in the 1960s: the increasingly uneven spread of Tory voters. The graph shows the minimal proportion of Conservative voters who would have to move seat within Britain if the Conservatives were to have an even distribution of the vote in that part of the UK at each and every General Election held between 1915 and 2015. In 2015 that proportion peaked at 19.9 per cent. When the UK becomes more polarised social pressures rise, people begin to separate more and more in their views, incomes and locations.

Look carefully at the map of the winners below (map furthest left) and what do you see? Six large clumps of red in a gently rising blue sea, with a newly formed yellow beach to the north. Climate change in politics is both gradual and increases the chances of very stormy weather in the years ahead.

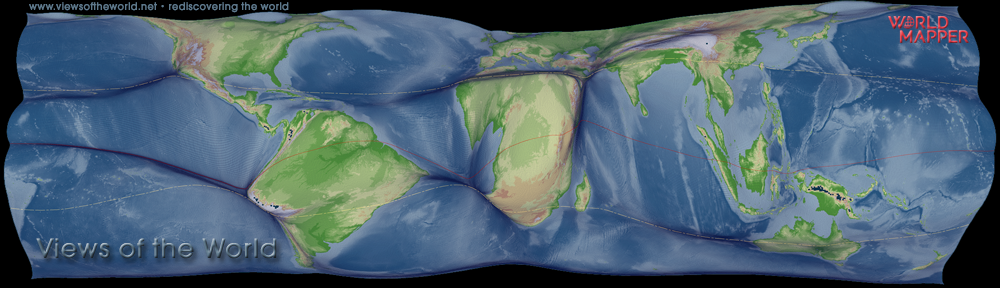

In these maps constituencies are drawn as cells in a beehive. The light purple cells are new land created in the May General Election, Labour seats that have emerged out of the Tory sea. Light blue is new sea (Tory seats that mostly used to be Liberal Democrat). The old orange tracts that were Lib Dem territory have suffered most from this heating up of the political climate.

This map of the voting hive, a hexagonal cartogram, was designed before the fifth periodic boundary review showing the political land area as it was in 2001. Where new constituencies were created in 2005 or 2010, a hexagon is cut in half with both halves representing a current seat. Where old ones have disappeared one-and-a-half hexagons now represents a seat.

The plate tectonics on this political map show electoral land disappearing, as the electorates of northern and Scottish cities shrink and so their politics looks a little like mountain ranges where the political peaks are also areas of greatest electoral subduction. But, in general, electoral geography changes slowly. In May, only in Scotland was there an earthquake.

A more detailed look at the voting change (see the two maps right of the map of the winning parties) shows only one constituency in England where there was a strong swing to the Conservatives (Bromsgrove, +10 per cent) and many where the swing to Labour was strong, but these were often in areas Labour already held. The Labour wipeout in Scotland had only one exception (Edinburgh South, swing to Labour, +4 per cent). Outside of Scotland there was only one seat in the rest of the UK where Labour lost more than a tenth of their 2010 support and that was to Ukip (in Clacton).

The dramatic 2010–2015 rise in the Tory segregation index was entirely due to changes in voting patterns within England; the Tory vote collapsed in Scotland long ago. The previous peak in Tory segregation was in 1918 at 19.3 per cent. That peak coincided with many other peaks of inequality in income, wealth and health in the UK. Today, we are again at new peaks of inequality and our voting reflects our highly divided and highly tensioned separating societies. Northern Ireland politics became highly segregated long ago. On the cartogram we have included (as two white hexagons) the loch around which so many colours are now found.

People in most of the UK are now living parallel lives. Their chances of meeting others who vote or do not vote like them have never been lower. In one half of England a majority of the population vote Conservative. In the rest of the UK a wider variety of parties are more popular and there are fewer Conservative voters to be found there than ever before. The UK is not four nations but two: The ‘might-haves’ and the ‘have-nots’, both governed – for now – by a very small group of ‘haves’.

The bibliographic details of the paper are:

- Hennig, B. D. and Dorling, D. (2015). In Focus: May 2015 – A Climate Change in UK Politics. Political Insight 6 (2), 20-21.

Article online (Wiley)

The content on this page has been created by Benjamin D. Hennig. Please contact me for further details on the terms of use.