Europe is currently suffering a deep political and economic crisis following years of turmoil and austerity measures that have disproportionately and brutally hit the most disadvantaged regions and citizens across most of the continent. At the same time, there has been a revival of nationalisms and divisions in this part of the world that, a decade ago, seemed to be united in diversity and moving towards ever-closer union. Concentrated poverty near to riches and profound spatial inequality have long been persistent features of all European countries, with disparities often being most stark within the most affluent cities and regions, such as London. In other parts of Europe levels of inequality and poverty have been reducing and are often much lower. However, the severe economic crisis and austerity measures have led, in many cases, to an enhancement of existing disparities. The following eight maps show how the regional geography has changed in the light of these developments:

Tag Archives: publication

In Focus: Trade Inside the European Union

The outcome of the referendum over the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Union raises some crucial questions over the country’s economic relationship with the remaining 27 member states. Economic issues over trade were among the most heavily debated issues throughout the campaign. Now that the decision has been made, existing ties with the EU need to be carefully considered in any future trade relationship with the European Union. In a contribution for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (December 2016, Volume 7, Issue 3) I mapped out Britain’s complex trading relations with the rest of the European Union and created a series of cartograms from the underlying statistics:

The outcome of the referendum over the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Union raises some crucial questions over the country’s economic relationship with the remaining 27 member states. Economic issues over trade were among the most heavily debated issues throughout the campaign. Now that the decision has been made, existing ties with the EU need to be carefully considered in any future trade relationship with the European Union. In a contribution for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (December 2016, Volume 7, Issue 3) I mapped out Britain’s complex trading relations with the rest of the European Union and created a series of cartograms from the underlying statistics:

In Focus: Where Art meets Science

Public spending cuts have been an important part of the political debate in Britain in recent years. In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (April 2016, Volume 7, Issue 1) Danny Dorling and I plotted the distribution of funding for the arts and universities in England.

Public spending cuts have been an important part of the political debate in Britain in recent years. In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (April 2016, Volume 7, Issue 1) Danny Dorling and I plotted the distribution of funding for the arts and universities in England.

The United Kingdom, and especially England, has become geographically extremely unequal. This inequality is not only seen in growing economic disparities within the population, but also becomes increasing visible across all parts of public life, such as science and education, as well as the arts. A report on arts funding in 2013, highlighted just how concentrated such funding was within London compared to the rest of the country. This represents the continuation of a now long-established trend.

In Focus: Europe’s uneven development

The British debate about the United Kingdom’s membership in the European Union comes at a time in which the economic woes of the continent have not fully overcome yet. In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (December 2015, Volume 6, Issue 3) Dimitris Ballas, Danny Dorling and I looked at the changing regional economic geography of Europe.

The British debate about the United Kingdom’s membership in the European Union comes at a time in which the economic woes of the continent have not fully overcome yet. In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (December 2015, Volume 6, Issue 3) Dimitris Ballas, Danny Dorling and I looked at the changing regional economic geography of Europe.

Europe is in an economic crisis – but the crisis is felt in very different ways in different places. Official unemployment rates are high, especially in the south of Europe, but joblessness is very low in places, such as Germany

The global inverse care law: a distorted map of blindness

“Eye care for all” is the motto of this year’s World Sight Day. But there are stark global inequalities in access to eye care. In 1971, Hart described the, ‘Inverse Care Law’ as the availability of good medical care varying inversely with the need for it in the population served. Hart was describing the situation in the National Health Service in Great Britain at the time in which he practiced as both a General Practitioner and an epidemiologist.

Two recently published articles demonstrate the ‘Inverse Care Law’ on a global level. The prevalence of blindness worldwide in 2010 was reported by the WHO and verified that low- and middle-income countries, as expected, have the highest prevalence of blindness and visual impairment. In stark contrast to this, a more recent report describes the,“Number of ophthalmologists in training and practice worldwide” providing global data for the number of ophthalmologists per county and demonstrates that despite a growing number in practice the gap between need and supply is widening.

The situation is also magnified within individual countries of high, middle and low-income. For example, in France, an inverse correlation was found between the number of ophthalmologists and the prevalence of low vision for subjects of similar age and socio-professional category and another example is in Kenya where of the 86 practicing ophthalmologists, 43 are based in Nairobi (personal correspondence). That equates to 50% of the countries ophthalmologists serving 8% of an already underserved population.

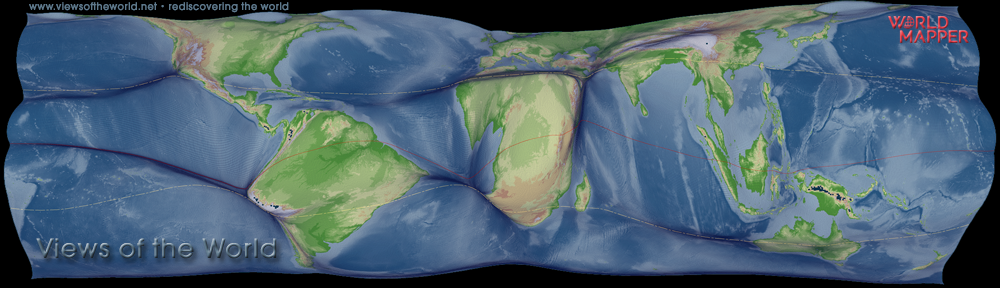

We have developed two cartograms to depict the data from these two papers using Gastner & Newman diffusion-based method. This allowed us to create density-equalised maps based on the absolute values provided in the papers. In the maps, each of the reference areas (WHO regions and countries) is resized according to these values. Larger areas represent higher numbers and smaller areas proportionally smaller data values:

In Focus: May 2015 – A Climate Change in UK Politics

Following the full cartographic roundup of this year’s general election earlier this week, here comes a related piece of research. In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (September 2015, Volume 6, Issue 2) Danny Dorling and I plotted the geography of an unexpected Conservative General Election victory.

Following the full cartographic roundup of this year’s general election earlier this week, here comes a related piece of research. In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (September 2015, Volume 6, Issue 2) Danny Dorling and I plotted the geography of an unexpected Conservative General Election victory.

What happened of most importance in 2015 was the rapid acceleration of a trend that has been underway in UK voting since 1979 and can be seen as having its origins in the 1960s: the increasingly uneven spread of Tory voters. The graph shows the minimal proportion of Conservative voters who would have to move seat within Britain if the Conservatives were to have an even distribution of the vote in that part of the UK at each and every General Election held between 1915 and 2015. In 2015 that proportion peaked at 19.9 per cent. When the UK becomes more polarised social pressures rise, people begin to separate more and more in their views, incomes and locations.