The British debate about the United Kingdom’s membership in the European Union comes at a time in which the economic woes of the continent have not fully overcome yet. In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (December 2015, Volume 6, Issue 3) Dimitris Ballas, Danny Dorling and I looked at the changing regional economic geography of Europe.

The British debate about the United Kingdom’s membership in the European Union comes at a time in which the economic woes of the continent have not fully overcome yet. In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (December 2015, Volume 6, Issue 3) Dimitris Ballas, Danny Dorling and I looked at the changing regional economic geography of Europe.

Europe is in an economic crisis – but the crisis is felt in very different ways in different places. Official unemployment rates are high, especially in the south of Europe, but joblessness is very low in places, such as Germany

The highest unemployment rates are mostly found in the austerity-stricken states: of Greece, Italy (especially in the south), and Spain. The Spanish region of Andalusia has the highest unemployment rate in Europe (34.8 per cent). In addition, there were a total of 30 regions with unemployment rates of over 20 per cent. These include all 13 Greek regions, as well as 13 regions in Spain and four in Italy. In contrast, the lowest observed regional unemployment rate in Europe in 2014 was 2.5 per cent, in two regions: the capital city region of Prague, in the Czech Republic, and the German region of Upper Bavaria (which includes the city of Munich).

The imposition of punitive financial sanctions did reduce regional unemployment rates in some countries and regions, but has hit some of the poorest in society. In Britain, there were 1,046,398 sanctions applied to Jobseeker’s Allowance claimants in 2012, encouraging people to take any job on offer or declare themselves self-employed.

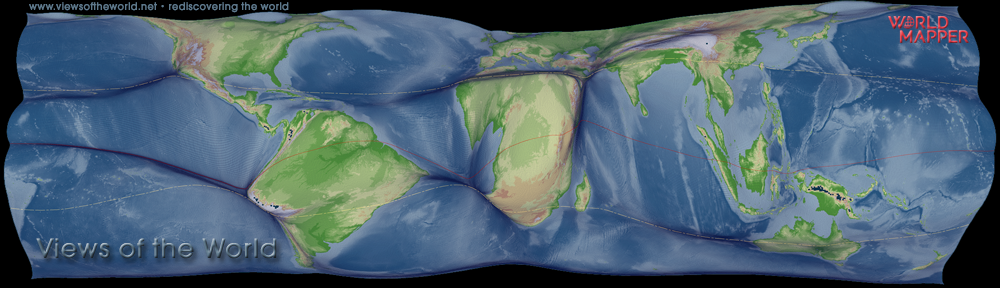

The following two cartograms reveal the absolute change in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) between 2007 and 2014, split into overall increase and decline as reported by the World Bank. All countries in these two maps are shaded using a rainbow colour scheme, starting with shades of dark red to demarcate the countries with the most recent association with the European Union and moving through to a shade of violet for the oldest member states. The area of each country is drawn in proportion to the total GDP or growth (in the left map) and decline (in the right map).

In all, 14 countries experienced a GDP decline: Italy, Spain, Greece, Portugal and Finland experienced the sharpest decline in total GDP and dominate the first map. However, in relative terms, Greece experienced the highest contraction with a GDP change of −25.8 per cent (total change between 2007–2014 as a proportion of GDP in 2007), followed by Andorra (−22.2 per cent), Croatia (−10.6 per cent), Italy (−8.9 per cent) and Portugal (−7.3 per cent).

These massive negative changes in GDP are also reflected in the unemployment rates in the regions of these countries as shown in the detailed regional map. Growth, in contrast, is centred on Germany, Turkey, Poland, the United Kingdom, France and Switzerland. However, it is worth noting that in relative terms, four countries registered a significant increase in growth of over 20 per cent: Kosovo (24.6 per cent), Turkey (24.5 per cent), Albania (24.1 per cent) and Poland (23.9 per cent).

Growth in GDP does not mean growth in wages. For example, in the UK median wages have not yet returned to their 2007 levels. Most of what growth there has been has only been reflected in greater wealth for a few, mostly a minority of those living in the south of England, where a housing inflation has resulted in a debt-fuelled mini boom. Behind every map are a thousand further issues on the ground.

The bibliographic details of the paper are:

- Hennig, B. D. Ballas, D., and Dorling, D. (2015): In Focus: Europe’s uneven development. Political Insight 6 (3), 20-21.

Article online (Wiley)

The content on this page has been created by Benjamin D. Hennig. Please contact me for further details on the terms of use.