The introductory words by Prime Minister Theresa May in the Conservative manifesto 2017 outlined the main focus for the government’s General Election campaign: ‘Brexit will define us: our place in the world, our economic security and our future prosperity’. But when it came to Brexit, the campaign itself featured little of political substance from either of the two main parties. The impact of the EU-debate on the (quite unexpected) election outcome is very complex, with the anticipated Conservative gains in Leave-voting Labour seats failing to materialise.

The introductory words by Prime Minister Theresa May in the Conservative manifesto 2017 outlined the main focus for the government’s General Election campaign: ‘Brexit will define us: our place in the world, our economic security and our future prosperity’. But when it came to Brexit, the campaign itself featured little of political substance from either of the two main parties. The impact of the EU-debate on the (quite unexpected) election outcome is very complex, with the anticipated Conservative gains in Leave-voting Labour seats failing to materialise.

In a contribution for the “In Focus” feature of Political Insight (September 2017, Volume 8, Issue 2) I looked at the outcome of the general election from the perspective of Brexit:

Indeed, the putative ‘Brexit election’ saw Ukip, the party that forced the EU referendum onto the political agenda, decimated. Ukip did not secure a single seat and their vote share went from 12.6 per cent in 2015 to 1.8 per cent. In general, the election was considerably influenced by tactical voting decisions which went at the cost of the smaller parties, according to post vote surveys such as the one conducted by Lord Ashcroft. The Green Party went from 3.8 per cent to 1.6 per cent and the Liberal Democrats lost slightly, going down to 7.4 per cent (from 7.9 per cent), despite managing to gain four more seats.

What has been described by some as a ‘return to two-party politics’ in Britain, might have been a mere pragmatic decision by the electorate to try to make their vote count more, rather than sacrificing it for a smaller party with little chance to get elected in a first-past-the-post system. A certain degree of (often informal) collaboration between so-called progressive forces, seemed to have played a considerable role in these tactical voting patterns, which helped the Liberal Democrats win seats, but aided Labour even more in gaining and regaining seats from the Conservatives. But two party-politics is far from being a reality. The results are rather a confirmation of the divided (or even confused) electorate, while the two main parties themselves appear equally divided (or confused) in their own approaches to Brexit.

This looks very different in Scotland. Scottish support of European Union membership in 2016 did not result in an overwhelming support of parties that are in favour of EU membership. The Conservatives, which lost 13 seats overall, were able to gain that same number in Scotland. A closer look at the vote shares suggests that the Tories benefited from a divisive debate about a possible new independence referendum that contributed to a split in the ‘progressive’ vote in Scotland between the SNP, Labour and the Liberal Democrats.

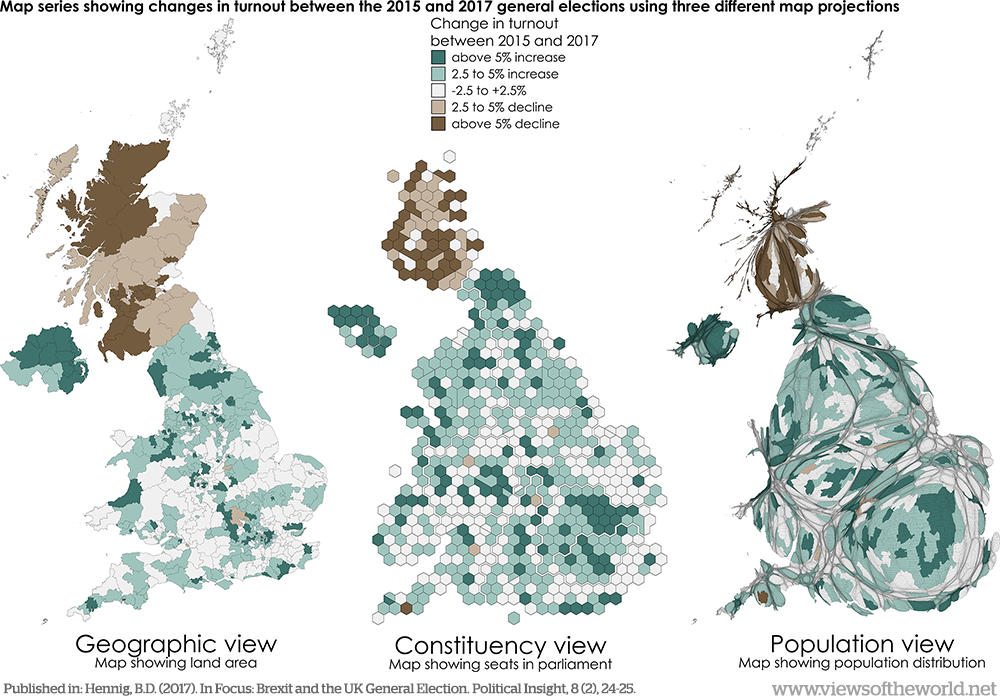

These dynamics must also be seen from the perspective of voter turnout, which had a particular impact on the outcome for the Scottish Nationalists. Overall voter turnout was comparably high at 68.7 per cent, with a turnout below 60 per cent found in the old industrial North of England and some parts of Scotland. More important, however, is the change in turnout compared to the 2015 General Election. Turnout was relatively high overall in most parts of Scotland. At the same time (unlike in most of the rest of the UK), turnout in Scotland went down compared to the 2015 General Election. In some areas turnout declined by more than five per cent. Having been called to the polling booth for the fourth time in three years might have led the Scottish electorate to experience voter fatigue but also to support the Conservatives, who appeared most trustworthy in preventing a new independence referendum. Linking the independence debate to Brexit did therefore not benefit the SNP.

While details about Brexit failed to become a major part of the election, the EU question still shaped the results. Labour’s message on pursuing a slightly less aggressive approach to Brexit negotiations (while still adding little more specific substance to it) allowed Jeremy Corbyn to make gains on both sides of the Brexit-spectrum. Labour increased their vote share, with 40.5 per cent not only considerably up from 30.5 per cent in 2015, but also close to the Conservatives’ vote share of 42.4 per cent. The additional 30 seats that Labour gained were largely won from the Conservatives, mostly in England, and spread over areas that had voted Leave as well as Remain in the EU referendum.

The General Election result returned Northern Ireland to the centre of British politics. The election resulted in an unprecedented bi-polar political landscape split between republicans and unionists, which widely also resembles the split between Leave and Remain vote in the EU referendum. The Democratic Unionist Party won an additional two seats. Their overall ten seats provided the crucial number for Theresa May to stay Prime Minister in a confidence and supply agreement between the two parties. Within the DUP’s electorate is a strong advocacy of Brexit, with all areas that voted Leave electing DUP candidates. Sinn Fein (who continue to abstain from the Westminster parliament) also increased their seats to seven and dominate the constituencies that voted Remain in 2016. Depending on the proceedings in the Brexit negotiations, Northern Ireland’s overall wider support for Remain might add to the conflicts that emerged with the DUP’s informal participation in the Conservative minority government.

Little detail was added to the Brexit debate during the election campaign. Nevertheless, the new political landscapes are clearly shaped by voting decisions that were influenced by the various implications of the EU referendum outcome for the different parts of the United Kingdom. That the results represent a turning point in British politics should not be taken for granted. Whenever the next general election will be, these patterns are very likely to change again, with Brexit and its wider consequences still playing a crucial part in it.

Further reading:

Thorse E., Jackson D., Lilleker D.: UK election analysis 2017: media, voters and the campaign. Bournemouth (The Centre for the Study of Journalism, Culture and Community).

The bibliographic details of the paper are:

- Hennig, B. D. (2016): In Focus: Brexit and the UK General Election. Political Insight 8 (2), 24-25. Full article online (Sage)

The content on this page has been created by Benjamin D. Hennig. Please contact me for further details on the terms of use.