Although the 2014 Paralympics started in the middle of the turmoil of the ongoing political crisis in the Ukraine, they went by rather smoothly in the end as most politically controversial tend to do. Putting politics aside, the Russian dominance that already became apparent at the Olympics (see this map) was even greater: The final medal count saw Russia at top of the table with not only the most medals (80), but also most gold (30), silver (28) and bronze (22). Germany came second with 15 medals (9 of them gold), closely followed by Canada with 16 medals (but only 7 gold which put them in third place in the rankings). Second-most medals, however, were won by Ukraine which is an peculiar detail given the current political situation. Britain won the first gold medal ever at the Paralympic winter games, and 19 nations managed to win at least one medal. Here is the Worldmapper-style view of all medals, showing the countries of the world resized according to their total medals won at the 2014 Winter Paralympics (as well as the individual success in each medal category):

Yearly Archives: 2014

European Youth Unemployment: A lost generation?

As shown previously on this website, unequal living conditions are one of the defining social problems of contemporary crisis-battered Europe. This weekend I attended the RondaForum 2014, Southern Europe’s forum on entrepreneurship and education, where this issue was discussed amongst young people from around the world who were seeking for new ideas to bridge the gap between the often bleak realities of Europe’s youth and the aspirations that are needed to create a sustainable basis for future competitiveness and growth. How big that problem really is amongst Europe’s youth can be seen from a look at the change in youth unemployment over the course of the financial crisis. Much of Europe’s youth is now being referred to as the lost generation, and in almost every European country youth unemployment has increased considerably between 2007 and 2012, as the following two maps show. They show the countries of Europe resized according to their absolute increase/decline in youth unemployment in these five years, with only Germany having a significant decline in youth employment in that period. Amongst those countries having a considerable increase, especially Southern Europe is standing out showing the growing North-South divide of the continent that highlight the challenges that initiatives such as the European Union’s Europe 2020 growth strategy face:

Sochi 2014 Olympic medal maps

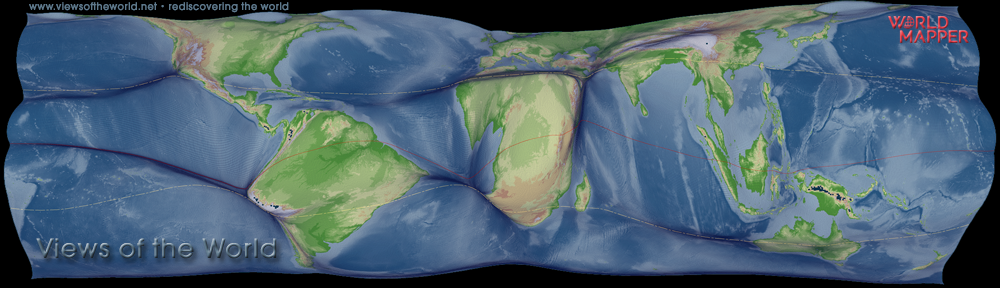

The politically controversial 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi (Russia) are history. What’s left as a legacy beyond the politics is the usual roundup of where the medals went and which nations managed to surprise or disappoint. The final medal count saw Russia being top of the table with not only the most medals (33), but also most gold (11) and silver (11). 26 nations managed to win at least one medal. Here is the Worldmapper-style view of all medals, showing the countries of the world resized according to their total medals won at the 2014 Winter Olympics (as well as the individual success in each medal category):

Unequal wealth: Income distribution gaps in Europe

Income inequality has become a wider acknowledged issue in the wealthy parts of the world which is no longer restricted to academic debate. A study commissioned by the IMF (Berg et al, 2011) acknowledges that “the trade-off between efficiency and equality may not exist” (IMF), referring to inequality one possible result of unsustainable growth. Europe has seen a steep rise in economic inequalities which have a huge impact of the people in the European nations. An OECD working paper (Bonesmo Fredriksen, 2012) states that “poor growth performance over the past decades in Europe has increased concerns for rising income dispersion and social exclusion”. It also concludes, that “towards the end of the 2000s the income distribution in Europe was more unequal than in the average OECD country, albeit notably less so than in the United States”, stressing that within-country inequalities are just as important if not more important than the between-country dimension. Both, however, are relevant in the current economic crisis and the again-growing divisions on the continent. As one of the reasons for these changes, the OECD paper states that “large income gains among the 10% top earners appear to be a main driver behind this evolution”.

Income inequality has become a wider acknowledged issue in the wealthy parts of the world which is no longer restricted to academic debate. A study commissioned by the IMF (Berg et al, 2011) acknowledges that “the trade-off between efficiency and equality may not exist” (IMF), referring to inequality one possible result of unsustainable growth. Europe has seen a steep rise in economic inequalities which have a huge impact of the people in the European nations. An OECD working paper (Bonesmo Fredriksen, 2012) states that “poor growth performance over the past decades in Europe has increased concerns for rising income dispersion and social exclusion”. It also concludes, that “towards the end of the 2000s the income distribution in Europe was more unequal than in the average OECD country, albeit notably less so than in the United States”, stressing that within-country inequalities are just as important if not more important than the between-country dimension. Both, however, are relevant in the current economic crisis and the again-growing divisions on the continent. As one of the reasons for these changes, the OECD paper states that “large income gains among the 10% top earners appear to be a main driver behind this evolution”.

The following two maps compare the share of income of the richest and poorest 10% of the population in Europe based on national-level data published by Eurostat (2013) (map legend ranked by quartiles). To show the data from a people’s perspective, the map uses a population cartogram as a base which shows the countries resized according to their absolute population. The maps give a look at how disparities exist not only between the countries, but also within each of them by showing, how (un)equal the distribution of income is in every country:

Into the big wide open: Think (twice) before you map!

A little bit from my archives which I never got around putting online before…here it comes: Last September I was invited to do a keynote at FOSS4G, OSGeo’s Global Conference for Open Source Geospatial Software. The event is the annual gathering of Open Source Geospatial Developers, Users and Leaders and was held at Nottingham’s new East Midlands Conference Centre, 17th to 21st September. The conference motto was ‘Geo for all’ because, as the organisers explain, “many people who work with geo software and maps find themselves becoming passionate advocates for the power of geography to make a difference: in government, business, travel, environment, crime reduction, social justice and communications to name just a few domains. Open Source Geo software makes this possible.”

So how does a geographer, working with geospatial software but being less so a developer, address a huge crowd of people who are little reluctant to see themselves as geeks and nerds? Instead of pretending to be as clever as most of the audience I took a slightly different stance, trying to bridge the gap between those on the programming side and those on the applied side – two groups which sadly rarely speak to each other. Traditional cartographers often see their field of work undermined (and threatened) by computerised methods to generate mapping products, while coders very often find the obsession with minute detail and ‘artisan’ cartography annoying. If the two worlds would come a bit closer together, and both sides speak a bit more with each other, the world of cartography and geospatial visualisations could benefit so much more. Addressing a more technical audience, I concluded that we should all think a little bit more before we start mapping, and that we should give a good mapping project a little bit more time than we often do these days – but more importantly of course: We should never stop mapping. These are the slides of my talk, of course including many maps: