Income inequality has become a wider acknowledged issue in the wealthy parts of the world which is no longer restricted to academic debate. A study commissioned by the IMF (Berg et al, 2011) acknowledges that “the trade-off between efficiency and equality may not exist” (IMF), referring to inequality one possible result of unsustainable growth. Europe has seen a steep rise in economic inequalities which have a huge impact of the people in the European nations. An OECD working paper (Bonesmo Fredriksen, 2012) states that “poor growth performance over the past decades in Europe has increased concerns for rising income dispersion and social exclusion”. It also concludes, that “towards the end of the 2000s the income distribution in Europe was more unequal than in the average OECD country, albeit notably less so than in the United States”, stressing that within-country inequalities are just as important if not more important than the between-country dimension. Both, however, are relevant in the current economic crisis and the again-growing divisions on the continent. As one of the reasons for these changes, the OECD paper states that “large income gains among the 10% top earners appear to be a main driver behind this evolution”.

Income inequality has become a wider acknowledged issue in the wealthy parts of the world which is no longer restricted to academic debate. A study commissioned by the IMF (Berg et al, 2011) acknowledges that “the trade-off between efficiency and equality may not exist” (IMF), referring to inequality one possible result of unsustainable growth. Europe has seen a steep rise in economic inequalities which have a huge impact of the people in the European nations. An OECD working paper (Bonesmo Fredriksen, 2012) states that “poor growth performance over the past decades in Europe has increased concerns for rising income dispersion and social exclusion”. It also concludes, that “towards the end of the 2000s the income distribution in Europe was more unequal than in the average OECD country, albeit notably less so than in the United States”, stressing that within-country inequalities are just as important if not more important than the between-country dimension. Both, however, are relevant in the current economic crisis and the again-growing divisions on the continent. As one of the reasons for these changes, the OECD paper states that “large income gains among the 10% top earners appear to be a main driver behind this evolution”.

The following two maps compare the share of income of the richest and poorest 10% of the population in Europe based on national-level data published by Eurostat (2013) (map legend ranked by quartiles). To show the data from a people’s perspective, the map uses a population cartogram as a base which shows the countries resized according to their absolute population. The maps give a look at how disparities exist not only between the countries, but also within each of them by showing, how (un)equal the distribution of income is in every country:

Tag Archives: cartogram

European Identities: The 2013 Eurovision song contest

The Eurovision song contest voting patterns is a popular theme for the analysis of European identity and culture. In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (September 2013, Volume 4, Issue 2) Dimitris Ballas, Danny Dorling and I looked at the voting patterns of this year’s contest that was held in Malmö (Sweden). It has long been argued that there are clear patterns based on geographical region as well as cultural and linguistic bonds and there has typically been labelling of groups of countries that give their votes to each other as ‘blocs’ such as the ‘Scandinavian bloc’, the ‘Mediterranean’, ‘Western’, ‘Eastern’, ‘Scandinavian’, the ‘Balkan’ bloc etc. It can also be argued that political considerations may also affect these voting patterns and this may be particularly interesting in the recent Eurovision song context with voting patterns possibly influenced by the on-going political and economic crisis in the European Union (EU). This map series puts a focus on those countries being closely associated with the EU, either by being current members or official candidate member states (or official potential candidate for EU accession) and/or signed up to any of the following agreements: European Economic Area, the Schengen Zone, the European Monetary Union. The maps are based on European states that currently meet at least one of these criteria, leaving the remaining participants of the song contest aside.

The Eurovision song contest voting patterns is a popular theme for the analysis of European identity and culture. In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (September 2013, Volume 4, Issue 2) Dimitris Ballas, Danny Dorling and I looked at the voting patterns of this year’s contest that was held in Malmö (Sweden). It has long been argued that there are clear patterns based on geographical region as well as cultural and linguistic bonds and there has typically been labelling of groups of countries that give their votes to each other as ‘blocs’ such as the ‘Scandinavian bloc’, the ‘Mediterranean’, ‘Western’, ‘Eastern’, ‘Scandinavian’, the ‘Balkan’ bloc etc. It can also be argued that political considerations may also affect these voting patterns and this may be particularly interesting in the recent Eurovision song context with voting patterns possibly influenced by the on-going political and economic crisis in the European Union (EU). This map series puts a focus on those countries being closely associated with the EU, either by being current members or official candidate member states (or official potential candidate for EU accession) and/or signed up to any of the following agreements: European Economic Area, the Schengen Zone, the European Monetary Union. The maps are based on European states that currently meet at least one of these criteria, leaving the remaining participants of the song contest aside.

World University Rankings 2013/14

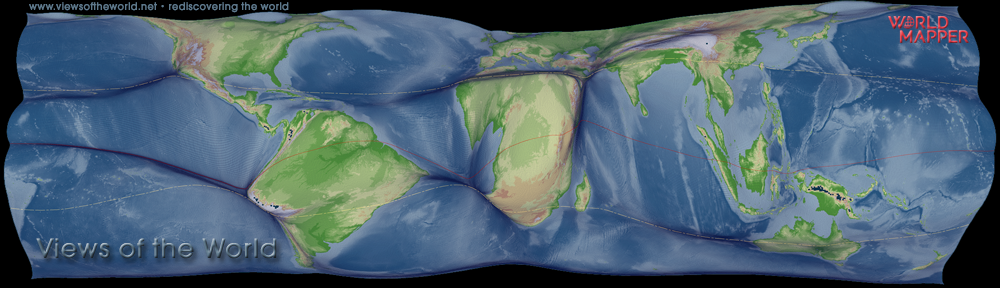

This feature was compiled in collaboration with Phil Baty of Times Higher Education and first appeared in the World University Rankings 2013-2014. In the following blog post we put the rankings results into a human and economic perspective (modified version from the original article). The two maps show the top 200 Universities from the Ranking displayed on two different kinds of gridded cartograms:

Political Landscapes of Germany in 2013

The following map series is a comprehensive overview of the individual second vote shares of each of the parties represented in the new parliament after the 2013 general election (in order of their absolute vote share) and a look at the change in votes compared to the Bundestagswahl 2009 for the party who were in parliament during the last term. I also mapped a few of the smaller parties that are most relevant in the public debate. Please note that the following page may take a while loading due to the large number of maps and their respective filesize. Continue reading

Turnout at the 2013 general election in Germany

The story of an election in a modern democracy has recently more and more turned into the story of a non-vote, as turnout at elections is on a general decline in many countries. That does not always reflect a certain libertarian strategy (otherwise the strive for anarchism would be stunningly on the rise), but can more likely be linked to an apolitical attitude. So how many Germans did choose to not cast a vote on this year’s general election (see the full results of the Bundestagswahl in this blog post)? 71.5% went to the polls last Sunday, so 29.5% of the electorate did not, which is slightly lower than the 29.2% non-voters at the 2009 election, though one can certainly not speak of an upward trend here. The following map gives an impression of this quite interesting geographical pattern that is far from evenly distributed across the country. The second map shows another group of voters who did not make their voice heard: The 1.3% of spoilt votes which again show a certain geographical distribution and are not completely evenly distributed. Even in the non-votes lie many spatial stories:

Bundestagswahl 2013: Electoral maps of Germany

Germany’s vote at this year’s general election has implications that reach much further than its national borders. CDU, the party of chancellor Merkel, could secure a massive victory getting 34.1% of the second vote share, though it narrowly missed an absolute majority of seats with its sister party CSU who won 7.4% of the votes (they are only standing in the Federal state of Bavaria). The former coalition partner FDP however missed the 5% mark (4.8%) that is needed to enter parliament, so that CDU/CSU now have to find a new coalition partner. Second largest party became that of Merkel’s contender Steinbrueck. SPD could secure 25.7% of the second votes. The only two other parties in parliament are Die Linke (The Left) with 8.6% of votes, and Die Gruenen (the Green Party) with 8.4%.

As often the case with electoral maps, the problem with conventional map depictions (as shown in the little thumbnail maps below) is the distorted perspective of the less populated areas. The maps shown in most of the media give the impression of an almost landslide victory of CDU/CSU. But while their good results are undisputable, the conservative CDU is traditionally strong in the rural regions, while SPD is stronger in urban areas. The following two maps show the largest shares of votes from each of the two votes. The first vote directly elects the local candidate into parliament, while the second vote determine’s each party’s total vote share in the Bundestag (Erststimme / Zweitstimme, read more about the electoral system in Germany at Wikipedia). When it comes to showing the real distribution of voting patterns in Germany, these two main maps give the more honest result of this year’s election: