Last week the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), a team of journalists from 45 countries, published leaked information about secret bank accounts at the Swiss branch of HSBC Private Bank.

The over 60,000 files relate to accounts holding more than $100 billion in total and provide information about more than 100,000 clients, their accounts and the amounts of money hidden in Switzerland, far away from their national tax authorities. The data was first given to the French government and the newspaper ‘Le Monde’ in 2008 already by a whistle-blower from HSBC and later shared with the ICIJ.

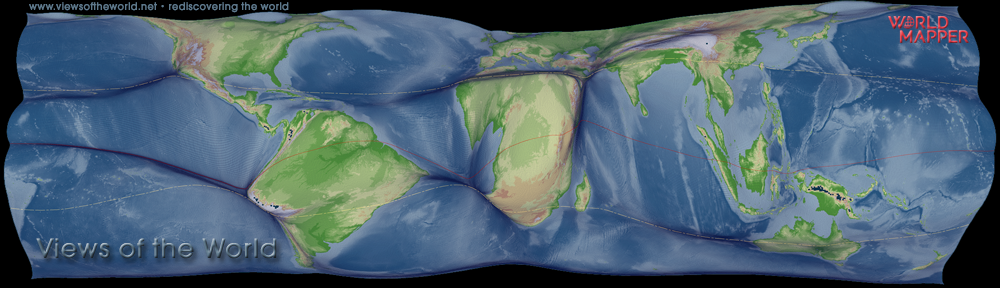

The two cartograms shown on this page reveal the global picture that emerges from the leaked data: They show the countries of the world resized according to the total number of clients and the absolute value of their accounts allocated to their respective country of origin:

Tag Archives: money

In Focus: The real size of Offshore Financial Centres

Featured

In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (December 2013, Volume 4, Issue 3) Jan Fichtner of the University of Frankfurt a.M. and I analysed the size of the foreign assets in the world’s largest offshore financial centres. All ‘offshore financial centres’ (OFCs) have one characteristic feature in common; they offer very low tax rates and lax regulations to non-residents with the aim to attract foreign financial assets. OFCs essentially undercut ‘onshore’ jurisdictions at their expense. The main beneficiaries are high-net-worth individuals and large multinational corporations that have the capital and expertise required to utilise OFCs. Beyond its geographical connotation the phenomenon of ‘offshore’ represents a withdrawal of public regulation and control, primarily over finance. Some important OFCs are in fact located ‘onshore’, e.g. Delaware in the USA and the City of London in the UK. However, historically many OFCs have literally developed ‘off-shore’, mostly on small islands.

In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (December 2013, Volume 4, Issue 3) Jan Fichtner of the University of Frankfurt a.M. and I analysed the size of the foreign assets in the world’s largest offshore financial centres. All ‘offshore financial centres’ (OFCs) have one characteristic feature in common; they offer very low tax rates and lax regulations to non-residents with the aim to attract foreign financial assets. OFCs essentially undercut ‘onshore’ jurisdictions at their expense. The main beneficiaries are high-net-worth individuals and large multinational corporations that have the capital and expertise required to utilise OFCs. Beyond its geographical connotation the phenomenon of ‘offshore’ represents a withdrawal of public regulation and control, primarily over finance. Some important OFCs are in fact located ‘onshore’, e.g. Delaware in the USA and the City of London in the UK. However, historically many OFCs have literally developed ‘off-shore’, mostly on small islands.

OFCs as defined by Zoromé (2007) are jurisdictions that provide financial services to non-residents on a scale that is excessive compared to the size and the financing of their domestic economies. The graphic shows combined data on securities (Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey by the IMF) and on deposits/loans (Locational Banking Statistics by the BIS) at the end of 2011. Capturing the two by far most important components of financial centres allows a reasonable approximation of the real size of OFCs while avoiding double counting. The larger the size of the circles on the map, the more foreign financial assets have been attracted to the particular jurisdiction. The vast majority of the almost US$70 trillion foreign financial assets are concentrated in North America, Europe and Japan. Areas with assets below $US50bn are not shown for their relative insignificance in the global context.

In Focus: The World’s Billionaires

In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (April 2013, Volume 4, Issue 1) Danny Dorling and I looked at the global geography of wealth. The map that I created for this feature displays data published by Forbes Magazine in spring 2012 (updated annualy). For 2012 Forbes counted 1153 billionaires across the globe (this figure includes families, but excludes fortunes dispersed across large families where the average wealth per person is below a billion). The total wealth of the billionaires was US$3.7 trillion – as great as the annual gross domestic product of Germany. Top of this league table is the US with 424 billionaires (or billionaire families), followed by Russia (96) and China (95). The following cartogram animation shows, how the distribution of billionaires and the distribution of their total wealth compares. Although there are only small changes between the two maps, it is quite apparent that the wealthiest in the wealthier parts of the world accumulate slightly higher shares of wealth than those living in the emerging economies such as China (though this may be some of the less worrying inequalities that exist globally):

In an article for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (April 2013, Volume 4, Issue 1) Danny Dorling and I looked at the global geography of wealth. The map that I created for this feature displays data published by Forbes Magazine in spring 2012 (updated annualy). For 2012 Forbes counted 1153 billionaires across the globe (this figure includes families, but excludes fortunes dispersed across large families where the average wealth per person is below a billion). The total wealth of the billionaires was US$3.7 trillion – as great as the annual gross domestic product of Germany. Top of this league table is the US with 424 billionaires (or billionaire families), followed by Russia (96) and China (95). The following cartogram animation shows, how the distribution of billionaires and the distribution of their total wealth compares. Although there are only small changes between the two maps, it is quite apparent that the wealthiest in the wealthier parts of the world accumulate slightly higher shares of wealth than those living in the emerging economies such as China (though this may be some of the less worrying inequalities that exist globally):

The State of the European Union

The European Union is an economic and political partnership between 27 European countries that together cover a large part of the European continent. As the EU website explains: “It was created in the aftermath of the Second World War. The first steps were to foster economic cooperation: the idea being that countries who trade with one another become economically interdependent and so more likely to avoid conflict. The result was the European Economic Community (EEC), created in 1958, and initially increasing economic cooperation between six countries: Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. Since then, a huge single market has been created and continues to develop towards its full potential. But what began as a purely economic union has also evolved into an organisation spanning all policy areas, from development aid to environment. A name change from the EEC to the European Union (the EU) in 1993 reflected this change.”

The Nobel Prize Committee recognised the achievements of the European Union by awarding the 2012 Peace Price to the project “for over six decades contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe“. But in the shadow of the European debt crisis Europe appears less the united with Euroscepticism gaining momentum in some countries. A 2009 study by the European Commission “Portugal and Hungary (both 50%) and Latvia (51%) contain the fewest people who feel optimistic about the EU’s future. The UK (53%), Greece (54%) and France (57%) also record noticeably low figures” (see page 212 in the accompanying report). “Euroscepticism in the United Kingdom has been a significant element in British politics since the inception of the European Economic Community (EEC), the predecessor to the EU”, concludes a Wikipedia contribution, which reflects the emotional and often – in either way – dogmatic nature of the debate in the most skeptic members of the Union. The EU appears to have become a welcome recession scapegoat.

But what is the European Union anyway. Rather than an alien construct imposed on the member states, it still is the agreed structure set up by its member states (for the good or bad, that is). The following series of maps gives a brief introduction into some of the key figures that shape the countries that are part of the EU and who are about the meet for negotiations on how to fund the European Union for the rest of the decade – having crucial implications on the role and purpose of the project. All maps shown here are cartograms based on national-level statistics. The first map is a population cartogram of the member states showing where how many people live (a more detailed perspective gives this gridded population cartogram of the EU):

In Focus: Financing the European Union

The Eurozone crisis has made monetary issues the focal point of political debate about the nature of the European Union, not just within members of the common currency but across the 27 states that constitute the EU. Discussions about emergency bailouts and transfers to support struggling economies have distorted the public perception of the costs and benefits of the Union.

The Eurozone crisis has made monetary issues the focal point of political debate about the nature of the European Union, not just within members of the common currency but across the 27 states that constitute the EU. Discussions about emergency bailouts and transfers to support struggling economies have distorted the public perception of the costs and benefits of the Union.

The actual EU budget is based on a multiannual financial framework, negotiated among the individual members and agreed upon at the level of European institutions. The current financial framework covers the period 2007–2013. Negotiations for the framework from 2014 to 2020 are under way. These discussions are greatly influenced by the implications of the current crisis. In a feature for the “In Focus” section of Political Insight (September 2012, Volume 3, Issue 2) Danny Dorling and I looked at the current financial framework and how the money is redistributed across the member states.

Continue reading

Continue reading